TV Guide 1959

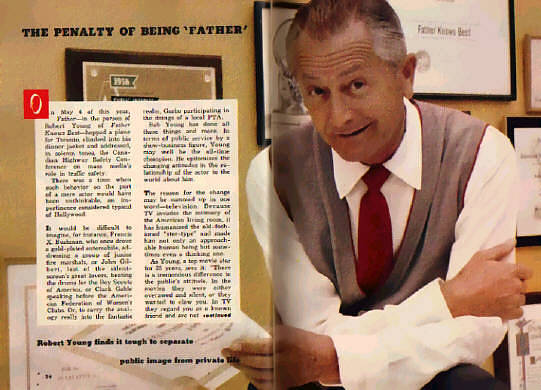

THE PENALTY OF BEING ‘FATHER’

Robert Young finds it tough to separate

Public image from private life

On May 4 of this year, Father-in the person of Robert Young of Father Knows Best-hopped a plane for Toronto, climbed into his dinner jacket and addressed, in solemn tones, the Canadian Highway Safety Conference on mass media’s role in traffic safety.There was a time when such behavior on the part of a mere actor would have been unthinkable, an impertinence considered typical of Hollywood.

It would be difficult to imagine, for instance, Francis X. Bushman, who once drove a gold-plated automobile, addressing a group of junior fire marshals, or John Gilbert, last of the silent-screen’s great lovers, beating the drums for the Boy Scouts of America, or Clark Gable speaking before the American Federation of Women’s Clubs. Or, to carry the analogy really into the fantastic realm, Garbo participating in the doings of a local PTA.

Bob Young has done all these things and more. In terms of public service by a show-business figure, Young may well be the all-time champion. He epitomizes the changing attitudes in the relationship of the actor to the world about him.

The reason for the change may be summed up in one word-television. Because TV invades the intimacy of the American living room, it has humanized the old-fashioned “star-type” and made him not only an approachable human being but sometimes even a thinking one.

As Young, a top movie star for 25 years, sees it: “There is a tremendous difference in the public’s attitude. In the movies they were either overawed and silent, or they wanted to claw you. In TV they regard you as a known friend and are not hesitant in stepping right up to engage in coversation.”

Young’s case is, of course, a special one because he plays the father of one of the most popular families in TV. Thus, as a Great American Father Image, more may be expected of him, perhaps, than any other TV actor.

And he is defenseless. He cannot hide behind the traditional “temperament” of the old-time movie star; he cannot plead unavailability. In short, as Father, he can’t say no.

And yet he has to. “Father” Young (who in real life has four daughters) now receives annually between 700 and 1000 bonafide requests to do everything from spearheading a Community Chest drive to addressing the high school graduating class of Podunk, Iowa. If he tired to fill all of them, the year would have to be a thousand days long and he would have to spend all his time speaking.

A television show by itself is tough enough. In playing Jim Anderson, Young, like most other regular-series actors, put in an average 12-hour day five days a week, 45 weeks a year. He must make certain personal appearances for the show, which do not have any connection with his public service activities. In addition, he is a community-minded man on his own hook.

At the present time he is active in the All Saints Episcopal Church of Beverly Hills, on the Parents Committee of the University of Southern California, on the board of the Bishop’s School in LaJolla, Cal., on the advisory board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation, and a trustee of the Cancer Detection Clinic of Los Angeles. None of these activities has anything to do with the blizzard of requests he gets as a result of TV.

Bob’s wife Betty apparently feels no strain at all. “Its not too rugged,” she says. “Bob manages to do a lot of things on the run. As for the trips, we try to make them pleasure as well as business. I love them. It’s good to get out of your realm.”

This may sound altruistic,” Young says, “but I derive a great deal of satisfaction from the few things I am able to do. And don’t think it doesn’t create a problem. Every time I have to refuse, it carries with it a suggestion of indifference. No matter what they ask, it’s sure to be vital to the askers, and they’re hurt when I ‘don’t consider it important enough.'”

Young and his studio handlers weigh each request very carefully in terms of maximum importance to the maximum number of people, and try to pick the ones that will spread the most good over the widest area.

“We don’t kid ourselves that we always pick right,” explains Screen Gem’s Jerry Hoffman, the man in charge of sifting the requests. “But we do the best we can. If I’d

let him, Bob would do everything. He wouldn’t even have time to sleep.

“One of the hazards is people calling or writing Bob at home. He’s a softy and the first thing I know he’s agreed to talk to the teen-age group of some village in the middle of nowhere.”

Young officially accepts approximately 50 public service speaking engagements a year. This does not include another 50 tape sessions which he does for such causes as the Red Cross, Community Chest, Cerebral Palsy Association, Heart Fund and March of Dimes. Nor does it include certain local projects that he sneaks past the management.

Occasionally he will shoot a public service film-like “Twenty-four Hours in Tyrantland,” a special Father Knows Best for the Treasury Department’s 1959 Savings Bond drive. But these grow increasingly rare because of the time and expense involved.

“People simply don’t realize that somebody has to pay for these things,” Young says sadly. “It is not so much the actual expense of shooting as the loss of time. It’s ironic. When I was at MGM I had plenty of time, but I didn’t get one request.”

Young is keenly aware of the change that the Father role has brought to him personally. “At first, when I began to realize how seriously people took me in Father Knows Best, I was badly frightened,” he says. “Understandably perhaps, I began to think the character was me. My wife finally brought things into focus. She advised me to know who I was and who Jim Anderson was, and not to confuse the two.

“However, the average viewer doesn’t make that distinction. As far as he’s concerned, Bob Young and Jim Anderson are one and the same man. And I have found myself constantly being pushed further and further into extroverted situations for which I am sometimes not qualified and, in fact, for which there is seemingly no justification at all. They may be suited to extroverted Jim Anderson but they are not necessarily suited to me. I am inherently shy. I don’t move easily in a crowd. So I had to do some serious work on myself in order to meet the requirements of what was expected. Now I’m more accepting. It’s no longer a problem, but something I have to live with.”

Written by Dwight Whitney